Research conducted by the British Heart Foundation has revealed a surprising fact: coronary heart disease kills twice as many women as breast cancer in the UK. Around 35,000 women are admitted to hospital following a heart attack in the UK each year – an average of 98 women a day, or four per hour – and around 24,000 will die from coronary heart disease (CHD).

Although heart attacks strike men at younger ages than women, survival rates are worse in women. Within five years of their first heart attack, 47% of women die, develop heart failure, or suffer from a stroke, compared with only 36% of men.

Why is that when a heart attack has never been more treatable?

The sex divide

The answer may lie in differences in treatment received by male and female patients, particularly when it comes to heart disease. The BHF study highlighted inequalities at every stage of a woman’s medical journey, partly due to the enduring misconception that heart attack is something that mostly affects men.

Women experiencing a heart attack are less likely to recognise their symptoms and are more likely to delay seeking help. Women wait, on average, 37 minutes longer than men to seek medical help when experiencing heart attack symptoms. This is likely to lead to worse outcomes for women and can reduce their chance of survival.

But the stereotype of the male heart attack victim can influence medical professionals too. A woman is 50% more likely than a man to receive the wrong initial diagnosis. Early misdiagnosis leads to a 70 per cent increase in the risk of dying.

Even with a correct diagnosis, a woman is less likely than a man to receive lifesaving treatments such as bypass surgery and stents. Aftercare is also neglected. Women in England and Wales are 2.7% less likely to be prescribed statins and 7.4% less likely to be prescribed beta-blockers when leaving hospital, despite the proven effectiveness of these treatments in lowering the risk of a subsequent heart attack or stroke.

These stark inequalities in awareness, diagnosis and treatment of heart attacks are causing needless deaths in the UK every day. It is estimated that more than 8,200 heart attack deaths in women in England and Wales over the last ten years could have been prevented if they had received the same standard of care as men.

Inequalities in clinical research

Sex inequality hides in plain sight today: most drugs are prescribed to women and men at the same dose, based on a default male patient. Many currently prescribed drugs were approved prior to 1993, with inadequate use of female animals in preclinical research and of women in clinical trials.

Women are and have been underrepresented in clinical research. After the Thalidomide tragedy in the late 1950s, there was a reluctance to include women of childbearing age in clinical trials and findings suggest that women continue to be underrepresented or excluded from important research.

Under-representation of women in clinical trials means that robust evidence on the safety and efficacy of some new drugs or devices may be lacking, leading to the underuse of life-saving therapies. The failure to distinguish between male and female subjects in basic and developmental research creates an understanding gap in how pathologies impact men and women differently.

Science has shown over and over that physiological and pathological functions are influenced by sex-based differences and that some treatments work differently in men and women. As we gain a better understanding of the relationship between sex and the incidence, prevalence, symptoms, age at onset and severity of disease, as well as the reaction to medicines, it becomes ever more important to act upon this knowledge and better target medical treatments to specific patient population groups.

Health equity is concerned with the attainment of equal opportunities for good health and high-quality health care for all people. It requires continuous efforts on behalf of society to address historical and contemporary injustices pertaining to the resources necessary for health, including access to quality healthcare, and safe living and working conditions.

Equitable representation in clinical trials is imperative for proper patient care and determining the safety, effectiveness, and tolerance of drugs for all consumers, and that includes women. Barbara Casadei, British Heart Foundation Professor and Honorary Consultant Cardiologist at the John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxford, is emphatic:

“Be aware and engage with your health and, if you can, participate in clinical trials. By doing so you will shine a light on cardiovascular disease in women and provide much needed evidence for its diagnosis and treatment in women.”

Inequalities in pre-clinical research

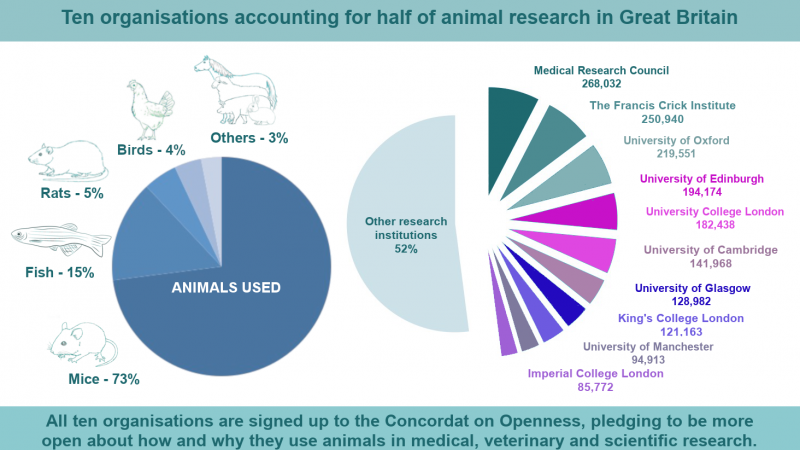

Sex bias starts high up the research chain because even in pre-clinical trials the female sex is underrepresented. The animal models used to understand diseases and discover and test new medicines are mostly male.

In labs, using male mice models is often the default approach. Male models are considered ‘easier’ because they are bio-chemically more uniform. Among 1,200 neuroscience papers from 2011 and 2012, only 42% reported the sex of the animals used, and when it was reported only 24% were female.

Ironically, for most applications, female mice tested through their hormonal cycle display no more variation than males do. In fact, there is actually, on average, a broader spectrum of variation in males for several different traits and behaviours, such as appetite and the use of an exercise wheel.

Reliance on male-only models to study diseases or develop drugs is a subtle and hard to see form of sexual discrimination. The lack of balance between the sexes in animal and cellular models makes applying the research to humans a lot trickier and is potentially undermining patient care.

However, this problem is increasingly being addressed. Prof Casadei explains:

“UKRI MRC has made a particular stance in recent years to make sure that both male and female mice are included in the studies when possible. Some disease models can only be reliably induced in one sex, but this is not likely most of the time.”

Regarding animal models for heart disease, Prof Casadei explains that the symptomatic differences seen in men and women can’t be evaluated:

“By law, animal models of disease are closely monitored to detect signs of pain or distress which would lead immediate euthanasia. A sudden coronary occlusion causing a heart attack can only be induced in an animal under general anaesthesia to minimise any kind of pain."

Prevention is key

In the meantime, Prof Casadei explains that the best way to compensate for sex bias is to be more aware of sex differences. Smoking and high blood pressure increase the risk of heart disease in women, as it does in men, and prevention is key to limiting the risk.

“Smoking remains a top prevention priority. Overall, during 2020-21, tobacco caused about as many UK deaths as COVID (and, unlike COVID, it’ll probably keep killing people at about the same rate throughout the 2020s).”

Heart attacks in women: what to look out for?

There are key differences between the symptoms in men compared to women. The British Heart Foundation lists the following as signs and symptoms of a heart attack in women:

- chest pain or discomfort that happens suddenly and persists, like pressure, tightness or squeezing

- pain can then spread to the left or right arm or to the neck, jaw, back or stomach

- sickness, sweating, light-headedness or shortness of breath

- sudden anxiety similar to that of a panic attack excessive coughing or wheezing

Last edited: 19 April 2022 16:48