Can we make sense of whale accents?

You might not be able to detect it from just reading my writing, but my speech would probably hint that I come from a distant country. And I wouldn’t be the only one to give away geographical origins by just muttering a few words. Accents, pronunciations and dialects have a universal topographic code. And this doesn’t only apply to humans. Birds, bats, monkeys, wolves, dolphins and whales are among some of the animals in which obvious accent differences were observed. Luke Rendell, marine biologist at the University of St Andrews, has worked for decades trying to decipher the meaning behind these accents in sperm and humpback whale populations.

“Even before my PhD started, killer whale vocal dialects had already been described, so I knew that at least one species of whale had different accents with different social units so I was inspired to go look for it in other species,” explains the marine biologist.

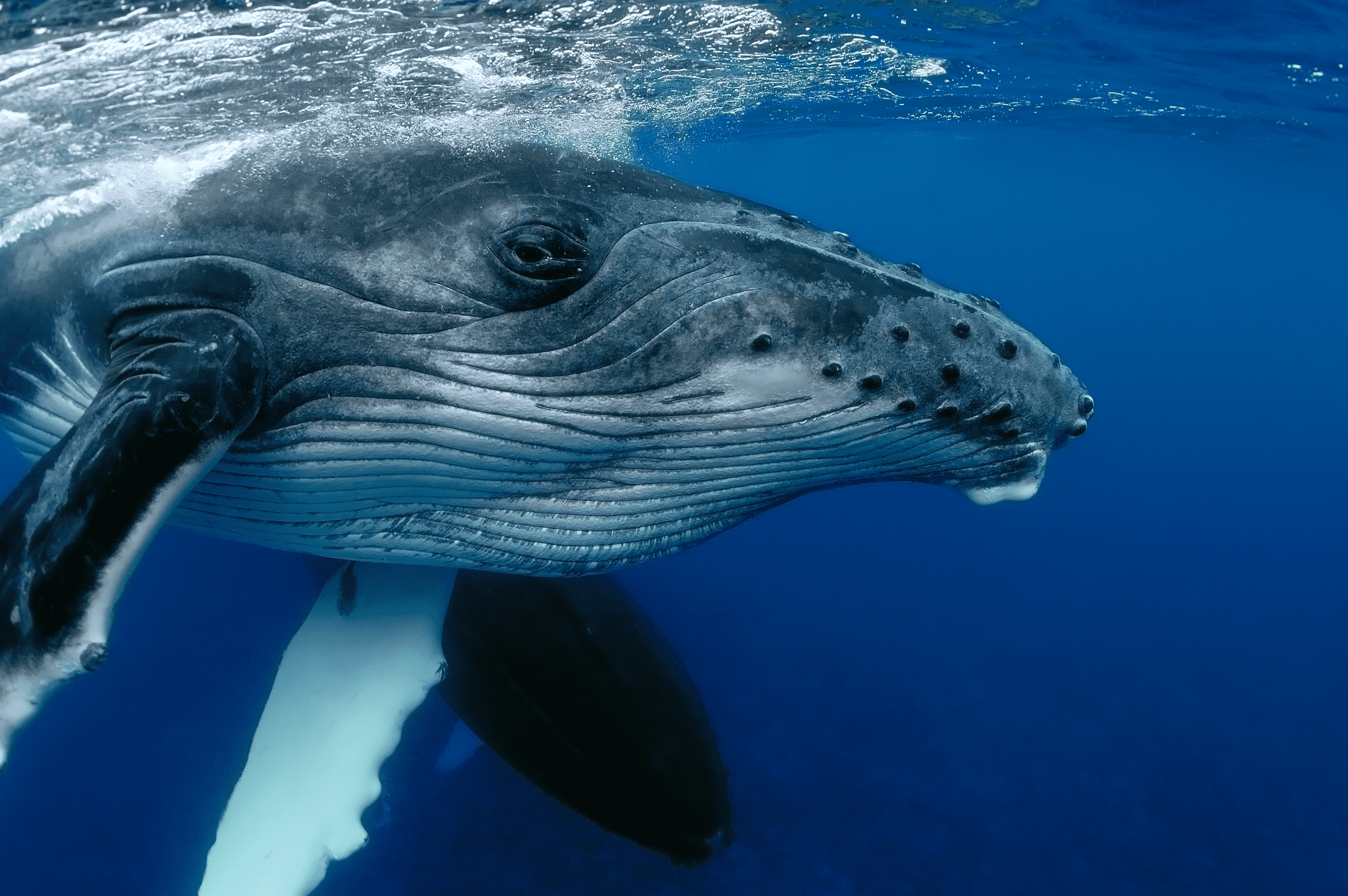

Sperm whales communicate with stereotyped patterns of clicks called codas. By studying these patterns from different groups of individuals from different part of the world, Luke tries to make sense of these dialects and identify the differences. “We tend to spend a lot of our time listening as much as we can and trying to piece things together from that,” clarifies Luke.

“We use underwater microphones called hydrophones that we can tow 100m behind boats. Increasingly there are new devices that you can leave in the water and place in strategic places happily recording away for 3 months to capture the sounds.”

How and why do these animals seem to develop these differences is another matter. For now, the answers are unclear.

“We still don’t really understand why the whales have these different speech habits. What we do know is that animals with different dialects are sometimes more or less likely to mate with each other. But from a communication perspective, we still have to make lots of inferences. We still need to study parameters such as when the whales make the sounds or whether they respond to the sounds that others make.”

Researchers often work with playback experiments. They try to fool the whales into thinking they are listening to another whale rather than a recording. Only that way is it possible to control the signal that is sent out and figure out the meaning of the response and what the signal is doing. “And that is pretty hard to do with wild cetaceans. You are in the environment - the weather is unpredictable, the whales are unpredictable. It is a very uncontrolled situation,” adds Luke.

However, working with aquariums isn’t an ideal either. First because the whales Luke work with don’t fit in aquariums - but also because the social and ecological context is very different.

“You have more control over what is going on in aquariums and what is heard by the animals. The experimental protocols can be repeated, and it is also possible to focus on individual animals and understand precisely their reaction but what you are seeing is going to be very different from what animals are experiencing in the wild. The social groups such as they are formed in captivity are nothing like the ones in the wild and the behaviours of the animals are very different as well. You can make inferences in captivity but you can’t hope to understand the full picture without studies in the wild.”

For now, the leading hypothesis is that whale accents have something to do with identity. Animals are signalling that they belong to a group – may that be to other members of the group to say that they are with them or to a different social group to keep a distance but “we are still really very far from understanding completely what is going on.”

I have to say that when I first heard about whale accents and speech I immediately got excited about the idea that we are somehow, one day, going to be able to decipher the whale dictionary and be able to have a conversation with them. But it is important to bear in mind that whale speech is probably quite different from human linguistics.

“I tend not to think about it in terms of language and words with specific meanings, which is a very human way to think about it,” argues Luke.” We’ve never really been able to demonstrate any kind of attribution between an arbitrary signal and anything in the real world; like a word can be attributed to a feeling or an object. I suspect that these signals are more about provoking an emotional or a bonding response. Much like singing or drumming the same thing with somebody can make you feel an emotion, promote feelings of wellbeing or belonging. Those kinds of bonds are very important to these animal’s lives.”

While it isn’t necessarily valid to compare whale song, whale sound and human speech, it is nonetheless true that in order to be able to speak, we have to be able to learn new sounds and these animals can learn new sounds. Why whales can, and humans can, but other animals can’t, could be a big clue to evolutionary conundrums.

Humpback whale song

More information:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Whale_vocalization

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/339243833_Vocal_sequences_in_narwhals_Monodon_monoceros

Last edited: 3 March 2022 14:47