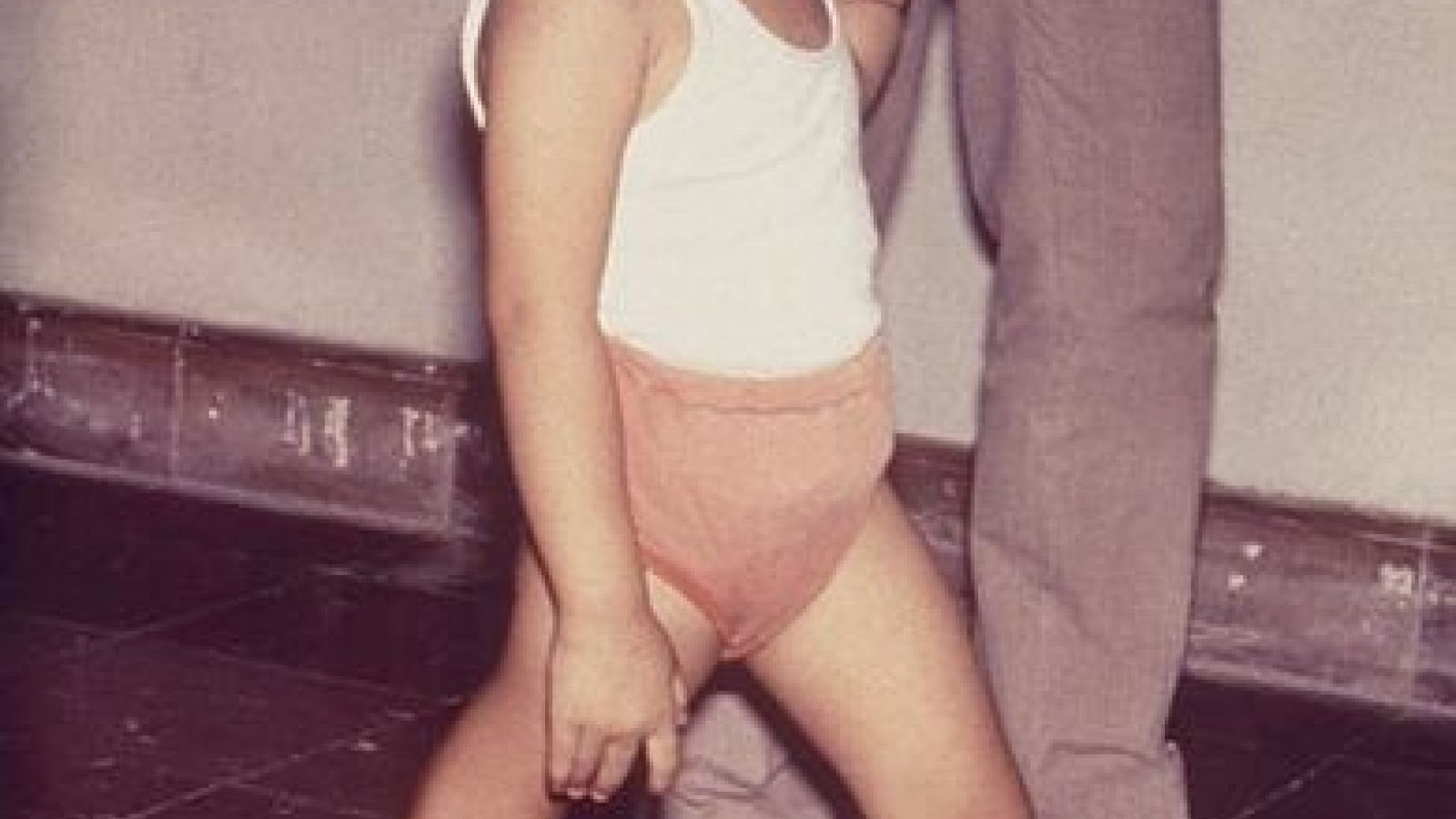

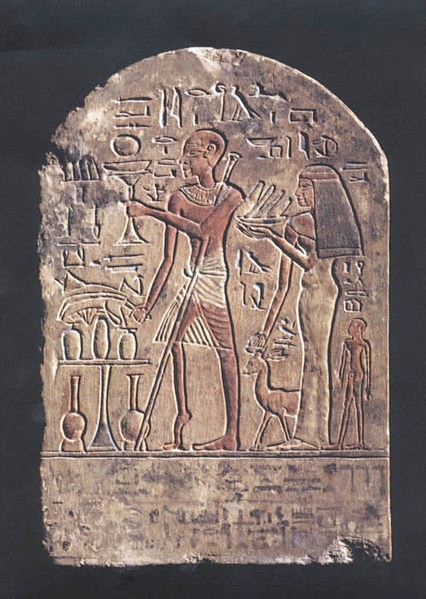

Poliomyelitis is a virus that has infected humans since the earliest of times – sometimes causing permanent paralysis. It mainly affects children under the age of five.

Polio was known to be an infectious disease since Karl Landsteiner and Erwin Popper’s famous experiments in 1908 showed that polio could be transmitted between animals.

It is transmitted from human to human, typically through drinking water contaminated with faeces containing the virus.

The polio virus can enter the body through the gut, damaging the nervous system in a matter of hours. This can lead to paralysis, and if the muscles that control breathing are paralysed, this can cause death from asphyxiation.

In the past iron-lungs supported breathing, allowing time for patients to recover from their infection, but sometimes the nerve-damage and paralysis were permanent.

Hundreds of thousands of people used to catch polio every year with one in 200 infections leading to irreversible paralysis and 5 to 10% of these people dying when their breathing muscles became immobilised.

Polio still cannot be cured but it can be prevented by vaccination.

Thanks to vaccination, polio cases have decreased by over 99% since 1988, from an estimated 350,000 cases then, to 416 reported cases worldwide in 2013. The reduction is the result of the global effort to eradicate the disease.

This success started with the search for a vaccine against the polio virus that began in the 1930s. Progress was initially held up by the difficulty of growing Poliomyelitis in cell-culture and the fact that there are three types of polio virus, so that an effective vaccine must protect against all three types.

Although it had long been suspected that polio was an infectious disease, definitive proof only came in 1908, when Dr Karl Landsteiner and Dr Erwin Popper managed to induce polio in monkeys by injecting them with extracts of the spinal cord of a boy who had died from polio. The disease could then be transmitted from monkey to monkey, providing an invaluable model of the disease. Eventually, it was possible to transfer a strain of the virus to the rat and to the mouse, which could be used in sufficient numbers to establish the existence and virulence of the polio virus.

In the 1940s Dr John Enders and his colleagues showed that the polio virus could be grown in human tissue, and this breakthrough was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1954. Even in the 1940s, the virus was too small to be seen with any available imaging technology, so there was only one way that Dr Enders could check that he had in fact extracted the virus from mouse brain tissue and grown it in culture. This was by injecting the culture fluid into mice and rhesus monkeys, where it produced paralysis typical of polio.

An inactivated (killed) polio vaccine (IPV) developed by Dr. Jonas Salk was first licensed for use in the US in 1955. A few years later a live attenuated (weakened) oral polio vaccine (OPV) was developed by Dr. Albert Sabin and became available in 1961.

The essential role of animal research in creating these vaccines was underlined by Professor Albert Sabin's 1956 paper in the Journal of the American Medical Association where he stated:

"approximately 9,000 monkeys, 150 chimpanzees and 133 human volunteers have been used thus far in the quantitative studies of various characteristics of different strains of polio virus. [These studies] were necessary to solve many problems before an oral polio vaccine could become a reality."

At first the vaccine virus was grown in cells taken from minced monkey kidneys. The vaccines were then safety-tested on rhesus monkeys, young mice, guinea pigs and rabbits, before being used on people.

Since the 1990s immortal cell-lines have replaced rhesus monkey kidney cells and a genetically modified strain of mouse that is susceptible to polio is now used to replace monkeys in safety testing.

Both vaccines are highly effective against all three types of poliovirus. There are, however, significant differences in the way each vaccine works.

The Salk vaccine has to be injected while the Sabin (oral) vaccine was taken as a drop on a sugar-cube.

Because oral polio vaccine is inexpensive, easy to administer, and produces excellent immunity in the intestine (which helps prevent infection with wild virus in areas where it is endemic), it has been the vaccine of choice for controlling poliomyelitis in many countries.[ So oral polio vaccine (OPV) was the main vaccine used from 1960 to 2000 to vanquish polio from much of the world.

On very rare occasions however, about one case per 750,000 vaccine recipients, the attenuated virus in OPV reverts into a form that can paralyse.

Consequently, as the incidence of wild polio diminishes, most industrialised countries have switched to injected polio vaccines, which cannot revert.

More than 10 million people are walking today, who would otherwise have been paralysed and an estimated 1.5 million childhood deaths have been prevented, through polio immunisation.

Unfortunately, endemic transmission is continuing in Nigeria, Pakistan and Afghanistan. Failure to stop polio in these last remaining areas could result in the re-emergence of the disease in other countries with as many as 200 000 new cases every year, within 10 years, all over the world. The breakdown of vaccination services in war zones such as Syria show additional risks of polio, and other diseases, breaking out.

As more and more countries switch to injected vaccines, scientists continue to improve vaccines using inactivated virus, to make vaccines cheaper and more effective. Research has already allowed mice to take the place of monkeys in safety-testing of polio vaccines and the hope is that a non-animal assay can be developed. But until then, and as long as polio persists, it is likely that animals will be used to test the safety of polio vaccines.

Read another fascinating article about polio treatment in Hungary in the Wellcome magazine Mosaic here: http://mosaicscience.com/story/hungary-cold-war-polio

Last edited: 10 March 2022 13:38