Depression is a debilitating and, typically, a chronic disease that affects about 264 million people, worldwide. It is a real illness that is a major cause of premature death in the world, especially among young men. Unfortunately, the general public often misunderstand depression as merely a feeling of melancholy and sadness.

The suicide rate in people suffering from depression is enormous. About 20% of depressed patients in the UK will attempt suicide, and about 12-15% of them will succeed. For 17-34 year-olds, suicide has become a leading cause of death in the UK, overtaking even road traffic accidents. This is a real concern, especially considering the toll the recent COVID-19 pandemic has taken on mental health.

While researchers have developed many effective therapies and drugs against depression there is still a long way to go in the search for truly effective treatments.

Antidepressants only work for two thirds of patients, can cause unpleasant side-effects and may have to be taken for many weeks before they begin to work.

Animals are playing a key part in finding new medicines, especially in the screening for potential new treatments.

“Although it is clear that all antidepressants are far more helpful than placebo treatments , and there’s no doubt talking therapies are useful, at the moment, there are no ideal treatments to fight depression,” states Professor Allan Young, Vice Dean (Academic Psychiatry) at King’s College London.

There are dozens of different antidepressant medications, but none of them are perfect. Many overlap in terms of their action and, most importantly, they don’t work for everyone. There isn’t one universal treatment.

About 30% of depressed patients will respond to the first antidepressant they are given, while a further 30% of patients will eventually respond to a treatment, or a combination of drugs, following multiple attempts at treatment. That leaves about 30% of depressed patients who don’t respond to any drug treatment at all.

“I was lucky enough to be prescribed antidepressants that were immediately effective with very little to no side effects,” recounts Melanie, a 30-year-old women living in London who was diagnosed with depression at the age of 17. “But I know a lot of people who were put on the wrong medication and suffered a lot of side effects, which can make it hard to stay on it consistently.”

Every existing antidepressant has a slightly different side-effect profile which can’t be ignored. Clare Stanford, Professor of Translational Neuropharmacology at UCL explains:

“This can be burdensome on the patient, especially considering it can take weeks or months before antidepressants start to take effect. These are not drugs like antibiotics that can be switched easily if the patient isn’t feeling better after a couple of days. With antidepressants, you have to persevere for weeks and then if it doesn’t work, you’ve lost a lot of time. We really need to reduce that delay.”

More fundamentally, current antidepressant drugs may not be treating the underlying disease, but the symptoms of that disease.

“This does mean that antidepressants don’t cure depression, they might simply be finding a way around the brain that bypasses the problem that’s going wrong with depression,” elaborates Prof Stanford.

There are many reasons to continue the search for new antidepressants. You want drugs that work quickly without a lag, you want drugs that work for the vast majority of depressed patients, and drugs with fewer side effects (and safer in overdose) to avoid patients stopping their treatments.

It is possible to study the illness in humans to try to find abnormal biomarkers of the disease that can later be targeted by drugs. But unfortunately, none has been found so far for depression and in any case it is often difficult to determine whether an abnormality is caused by the illness itself or is an adaptive response to the treatment the patient is taking.

“At the moment, there is no alternative to using animals in that research,” states Dr Sarah Bailey, Senior Lecturer of Pharmacy and Pharmacology at the University of Bath.

“Psychiatric illnesses are inherently human in nature, what we’ve tried to do is model certain facets of the disease in animals,” explains John Kelly, Professor in Pharmacology and Therapeutics at NUI, Galway.

It is possible to experimentally induce modifications in the brain of laboratory animals or behaviour changes that are similar to those observed in humans.

“But because we don’t really know what’s wrong in humans in the first place, this approach can be tricky,” adds Prof Stanford. “To find new antidepressants, a more successful line of research is directly studying in animals, drugs with known beneficial effects in humans, to understand how they work. Once you’ve got a handle on the sort of action that all antidepressants have in common, then you can develop better, more precise and targeted drugs, with fewer side effects.”

That said, this does tend to select compounds that work in very similar ways. It is very difficult to break new ground and discover an antidepressant drug which works in a completely different way using this approach. Major breakthroughs in drug discovery usually happen by chance. The first antidepressant was discovered in such a way. It was originally used to treat tuberculosis, but an uncommon side effect caught the physicians’ attention. The drug induced euphoria in patients, an unwanted effect for tuberculosis patients, but exactly what was needed to treat depressed patients.

Detecting a change of mood in animals is trickier.

“Obviously, an animal isn’t going to tell you it feels depressed or unhappy, but you do get changes in behaviour which are similar to humans suffering from depression,” explains Professor Young.

These changes can be a loss of interest in food and sex, for example, which can be measured to an extent. However, there is one test that has shown the same results over and over again for all known antidepressants in humans.

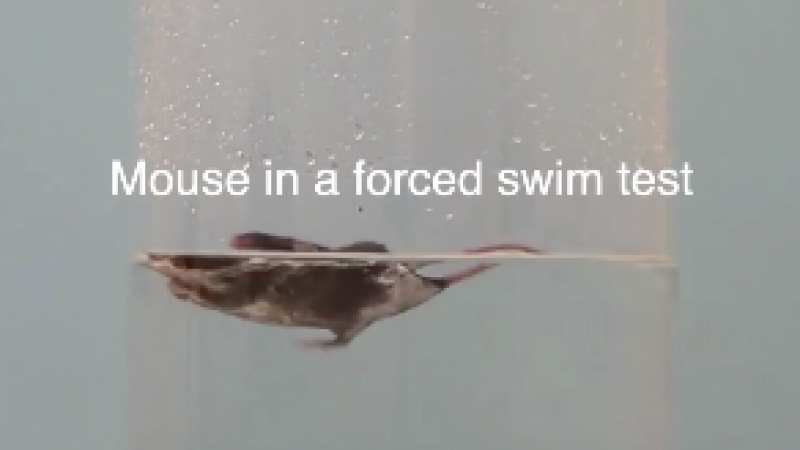

This is the Porsolt, or forced swim test. Mice or rats are gently placed in a small tank of water where they swim around to find a way out. When they understand there is no way out, they develop a floating posture. The rodents are naturally buoyant, so they don’t sink. Antidepressant drugs keep animals swimming and delay the onset of the floating posture. The animals treated with an antidepressant tend to swim around and explore the perimeter of the tank for much longer, sometimes, two to three times longer.

“The forced swim test is a widely validated behavioural procedure for predicting antidepressant efficacy. It is highly reliable, very sensitive to antidepressant drugs across a wide range of different classes of medicines. It is the best model to test new potential antidepressant compounds,” explains Dr Bailey.

“All the drugs that have a beneficial effect on depression in the clinic have shown exactly the same effect on the behaviour of rats and mice in this test. So, if a new molecule didn’t show prolonged swimming in rats and mice, it’s pretty certain that it wouldn’t attract the interest of industry for any further development because that test is such a gateway as an indicator of an antidepressant effect in humans,” elaborates Prof Stanford.

However, the forced swim test is rarely, if ever, used on its own to assess a potential new drug.

“It is just one readout. You can’t rely just on one test; you need to use lots of different readouts across a multitude of different tests in order to get a good idea of what is happening. It is the same for humans, one test won’t tell you if a human is depressed or not,” explains David Slattery, Professor of Translational Psychiatry, Goethe University Frankfurt.

Whether as a fundamental treatment of a condition or as a treatment for the symptoms arising from that condition, we need new and more effective drugs, that act more quickly with fewer side-effects. Animals will continue to help us find those drugs.

Please see our factsheet on the forced swim test.

Last edited: 27 October 2022 18:33