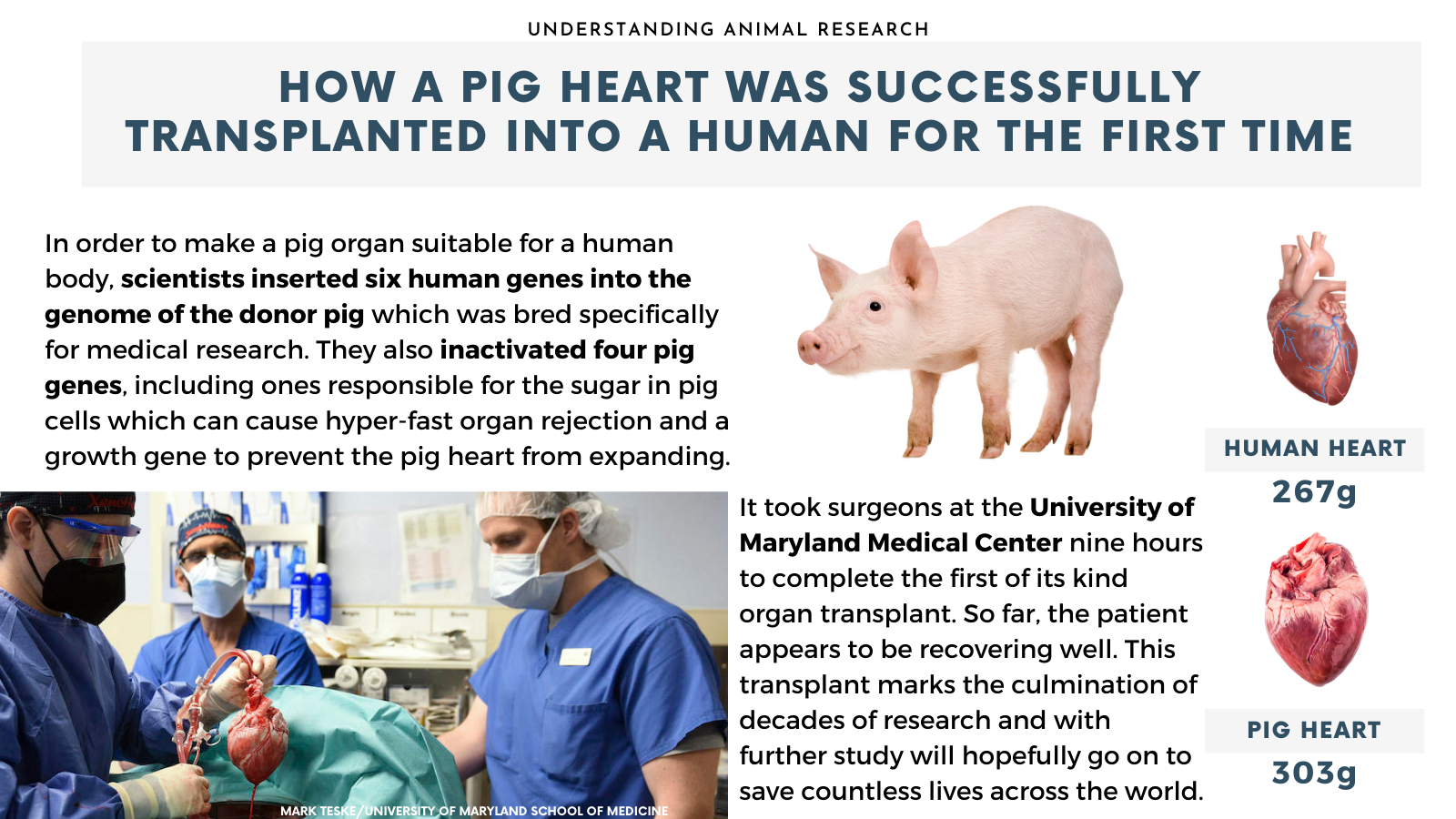

First-ever pig to human heart transplant

The big news story from this month is of course the first-ever animal to human heart transplant. In a culmination of decades worth of research, the heart of a genetically altered pig was successfully transplanted into a patient (David Bennett, 57) on 7 January 2022 at the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

The heart came from a pig bred with ten genetic alterations. While pig hearts are anatomically like human hearts, albeit slightly larger, scientists had to insert six genes into the genome of the donor pig to help the human body accept the organ and inactivate four pig genes with the aim of preventing organ rejection in the patient and ensuring the pig heart remains human-sized.

The pig-heart transplant was Mr Bennett’s last option. He had been diagnosed with terminal heart disease and could not receive a mechanical heart pump due to an irregular heartbeat and was not allowed a human-heart transplant. Given that he would have died, the US Food and Drug Agency (FDA) granted the research team special permission for performing this experimental surgery.

Aside from two legally brain-dead people receiving successful kidney transplants from genetically modified pigs in 2021, most research into xenotransplantion has taken place in non-human primates. While it is still too soon to know the long-term success of Mr Bennett’s operation, the research team hope this research will lead to the consideration of xenotraplantation clinical trials.

Source: NewScientist

Read our article 'Pig to human heart transplants: how did we get here?' for more information about the history of xenotransplantation.

Covid-19 research

Recent studies involving animals indicate that the Omicron Covid variant is more likely to infect the throat than the lungs as seen in previous variations of the disease. This would explain why Omicron is less deadly, but more transmittable compared to a virus the replicates more in the lungs, which would be more dangerous but less transmittable.

Studies in mice and Syrian hamsters have shown that Omicron leads to ‘less severe disease’ i.e. animals infected with Omicron lose less weight, have less infection in the lungs and experience less severe pneumonia than animals infected with previous variants.

Mice and hamsters have been used consistently in Covid research. Mice have been used to test the safety and efficacy of all the Covid vaccines approved for use in the UK and to answer questions about the disease. Hamsters infected with Covid display similar symptoms to humans and so have been used to answer questions about serious infections and to develop treatment strategies.

Source: Guardian

View this post on Instagram

Research into Covid nasal sprays continues, and a recent study involving mice illustrates that the animals who received the nasal spray and were subsequently exposed to the virus remained 'entirely free of viral antigen'. If this research proves successful in human clinical trials, the technology could be used to protect high-risk individuals from infection.

Source: Daily Mail

Repairing broken hearts

Immune cells of mice have been temporarily reprogrammed to repair damaged hearts by removing scar tissue using the mRNA technology also used in creating some of the Covid vaccines.

T-cells are immune cells that recognise and destroy viruses, they can be reprogrammed to target different cells so long as they are given the appropriate receptor. By delivering mRNA genes into the body, antibodies can attach themselves to these T-cells and temporarily turn them into cells that target collagen production. The research team used this technology to significantly reduce scarring in mice with damaged heart tissue. If further research proves successful, this technique could not only be used for treating scarring in other organs but to also target specific cells to treat all kinds of diseases.

Source: NewScientist

For more information on mRNA technology, you can read our article 'RNA vaccines: a new tool against Covid-19' on how it’s been used in Covid vaccines.

Insights into Cystic Fibrosis

The survival of mice with cystic fibrosis has been dramatically improved thanks to a partial bone marrow transplant. The transplant allows the body to make healthy monocytes, immune cells which develop in the body’s bone marrow and protect the lungs, guts, and other organs. Monocytes are defective in people with cystic fibrosis, so this transplant aims to restore regular monocyte function. If found successful in larger mammals and then clinical trials, this could lead to a treatment that gives patients long-lasting relief from cystic fibrosis symptoms.

Source: NewsMedical

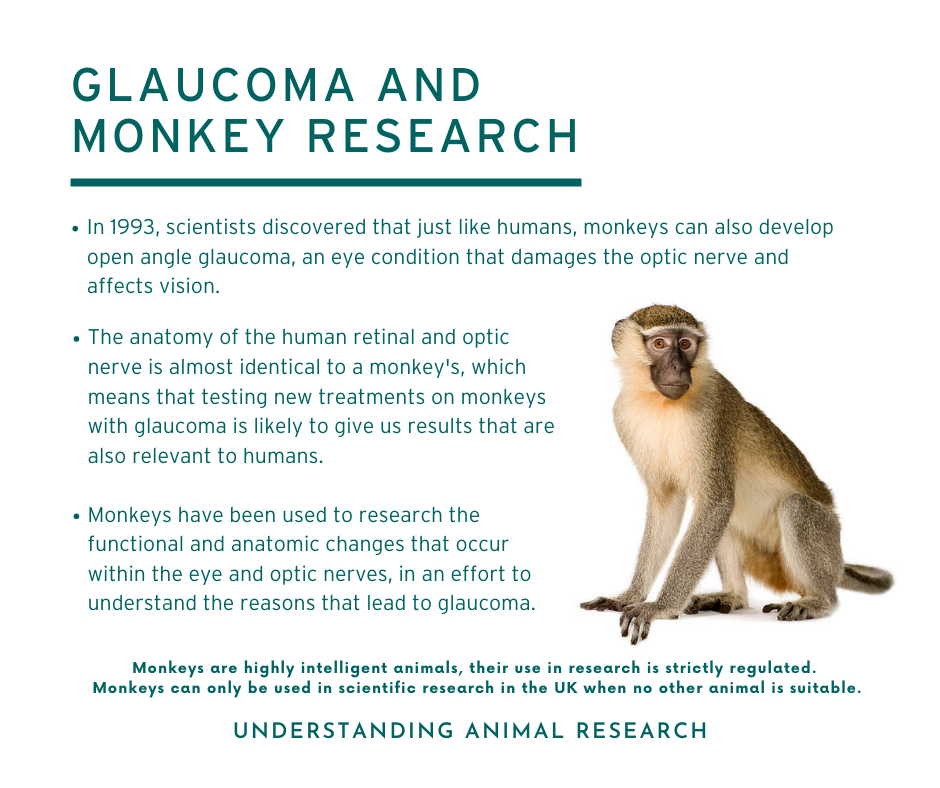

Cervical cancer and Glaucoma awareness

This month we recognised Cervical Cancer Prevention Week and Glaucoma Awareness Month. Take a look at our infographics to find out how animal research helped develop the HPV vaccine and how monkeys have been used to advance our understanding of Glaucoma.

View this post on Instagram

Openness in animal research

If you would like to know more about why animal research is carried out in the UK, you can download the Academy of Medical Sciences' booklet of animal research case studies where you can find out how mice, rats, zebrafish, dogs, cows, and computers are being used to improve animal and human health.

You can also see what it is like inside an animal research facility in this new video by The Babraham Institute.

Last edited: 4 August 2022 16:27