When talking about the ‘3Rs’ of reduction, replacement and refinement which govern and guide animal research in the UK, it can be hard to quantify successes – how can you count an experiment which didn’t take place? Nevertheless, there must be something going on. Research and development expenditure by the pharmaceutical industry has increased by £1 billion since 2002, yet the Home Office figures for animal use by commercial organisations have stayed largely unchanged with around 1.5 million procedures a year. If R&D is increasing then surely the numbers should be higher – they should be using more animals?

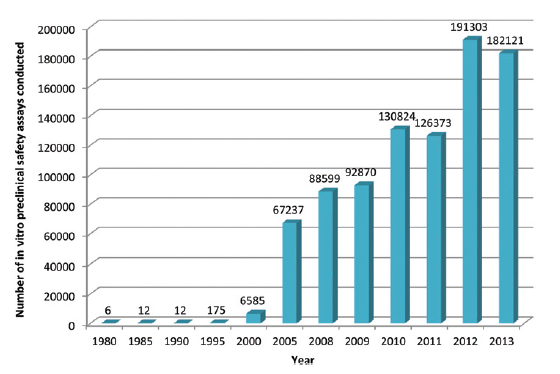

This is a topic which the UK’s pharmaceutical industry umbrella body, the ABPI, set out to explore by questioning its members, with the results appearing in this paper in the journal Toxicology Research. What they found is that development and uptake of alternative technologies has been steadily gaining pace, culminating in an exponential rise since the millennium. Indeed more than 70% of all in vitro assays captured by the survey were used since 2010, peaking at just over 190,000 in 2012.

To be clear, reducing animal usage is not as simple as swapping out an animal assay for an in vitro alternative. Alternatives can’t always tell us, for instance, if a compound will cause DNA damage leading to cancer, but they can some of the time, so we may be able to avoid using animals in the case of compounds with well understood adverse pathways. Likewise, many of these in vitro techniques will have been used alongside animal studies to build up a picture of a drug’s safety or otherwise. However, there can be no doubt that investment in alternatives is starting to pay off.

The reasons for this increasing uptake are slightly opaque, with the authors suggesting it may have been partially spurred by the International committee on Harmonisation changing its guidelines for pharmaceutical development. Ongoing ICH revisions and their adoption tend to be driven by research into and validation of in vitro alternatives conducted by and published in collaboration between pharmaceutical companies, CROs and academia, so in other words as alternatives are confirmed as validated they become the new norm.

In addition to this, there are inherent disincentives to using animals such as ethical costs, bureaucracy or the financial burden of maintaining animal houses, with vets and animal techs. Even the animals themselves are expensive. If there were a better and cheaper way of ensuring drug safety, you can bet the pharmaceutical industry would embrace it with some enthusiasm.

So it has been with skin tests, such as EpiSkin, which uses reconstructed human epidermis as a replacement for the rabbit skin irritation tests. However, as the paper notes:

“Many of the in vitro assays that have been developed in areas such as genetic toxicology and electrophysiology score low on utility – this could be due to a high level of false positive results which makes extrapolation to the human situation difficult. In addition, the reliability of in silico testing to predict safety signals remains in its infancy and has even been called into question in a recent paper from Cook et al. (2014)."

In all, this paper is a progress report with encouraging things to say about the pharmaceutical industry’s direction of travel. The bottom line is that they still very much need to use animals in this area of research since ‘alternative’ assays simply can’t model complex biological systems yet, but they clearly are pressing ahead to make whatever gains they can using available technology. Further progress will come from the same place as today’s successes – collaboration between industry, academia and bodies such as the National Centre for the 3Rs, creating, validating and normalising the use of alternatives to animal models.

Last edited: 5 April 2022 12:01