How social isolation affects your body

Could post-covid-19 social isolation really be affecting us that much? Mouse studies have shown that being cut off from others can cause profound physiological changes in our bodies that might explain the sudden mood swings and memory gaps you have been experiencing.

The emergence of the Covid-10 epidemic has forced global reactions and the isolation of populations to avoid spread of the disease. But as the weeks passed, people started experiencing signs of stress. Social isolation seemed to be weakening attention span, productivity and deteriorating metal health. But could these symptoms really be linked to a simple decrease in social contact? As it turns out, scientists have an answer. The role of social isolation had already been extensively studied in animals.

Isolation has an immediate effect on the body by increasing the levels of the stress hormone, cortisol which regulates fundamental metabolic pathways in the body, from sugar levels, blood pressure to memory formation.

Exposure to chronic stress can affect growth, brain function, the neurochemical and neuroendocrine system, and the immune system. It is therefore unsurprising that social isolation causes systemic physiological, anatomical and behavioural changes in animals and humans.

And one of the first organs affected is the brain. Chronic social isolation can cause deep changes in the brain. The chemical balance of the nervous system is disrupted.

After only two weeks of isolation, changes in neuropeptide levels in the mouse brain are responsible for an increase in aggressiveness. Growth factor in the brain decreases causing neurones of the sensory and motor areas of the cortex to shrink by up to 20%. And these changes can have drastic consequences.

Mice that have been isolated have a higher risk of developing anxiety and depression, with symptoms sometimes appearing only 12h after isolation. Just like chronic stress, social isolation is a major risk factor of several psychiatric disorders.

And these anxious and depressive behaviours can be correlated to a decrease in activity of several genes linked to neuroplasticity in the hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex which is turn cause memory impairments.

Social isolation is particularly hard on the adolescent brain. Mice isolated during that crucial period of development do not develop as effective brain plasticity. The dendritic spines of their neurones remain immature. Social isolation at a young age has long-term consequences for brain development and behaviour. Impaired cognitive development and a change in the prefrontal cortex of these isolated young animals explains their abnormal behaviour in adulthood.

Scientists have found a direct link between isolation in adolescence, abnormal development of the prefrontal cortex and the appearance of so-called habitual behaviours in adulthood. Social isolation could therefore lead to excessive dependence to habits, addiction and obesity.

And this, again, doesn’t come much as a surprise. Social isolation has been found to also affect the dopaminergic system in the brain that causes food and drug addiction. After only 24h in isolation, dopaminergic neurons in the midbrain of isolated mice activate when they seek contact. After being alone for just a short period of time, social interaction is perceived as a reward by these social animals.

Isolation of mice leads to a state of aversive "loneliness" that increases motivation for social engagement. And the neurons react to social contact the same ways as they would for any addiction. Isolating a mouse creates a craving for social interaction, just like a hungry mouse would for food.

And interestingly, these results can be replicated in humans. The development of social media is a clear example of how powerful that drive can be in humans. It is no coincidence that social isolation has been inflicted as a form of punishment in human societies throughout the ages. People isolated are more likely to experience high level of chronic stress and die prematurely.

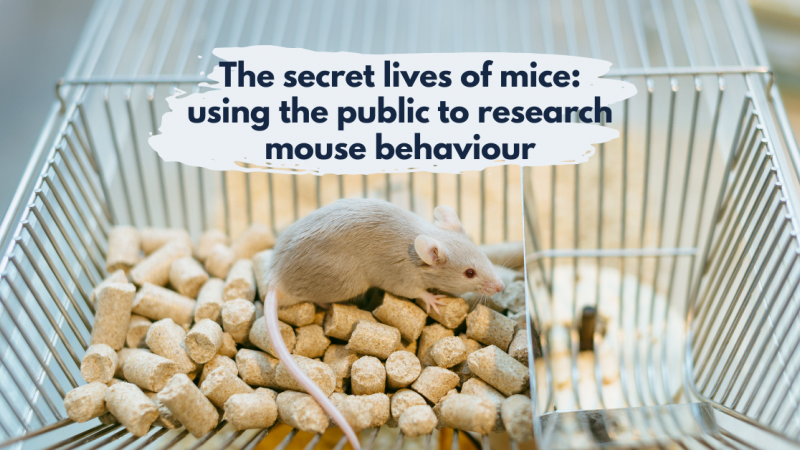

These findings suggest that there is a common mechanism to mice and humans alike, and probably all social animals, behind the need and the physiological effects of social contact. And scientists have taken advantage of these similarities for decades to model human disease in the mouse.

Social isolation has been a tool to model depression, social disorders, anxiety in mice. These models have been instrumental in finding ways to fight these pathologies in humans just as much as they have been essential in advancing our understanding of the causal links between social processes and health.

But if these studies have taught us one thing is that social interactions are important for mice and that a particular attention should be brought to their social needs in the lab. And again, scientists are ahead on this issue.

It is widely recommended that mice and rats be housed in social groups when possible. The European Directive that regulates the use of animal in research states clearly that all restrictions to the physiological and ethological needs of the animals should be kept to a minimum. And that includes the need for interaction.

Last edited: 28 July 2022 16:17