Around the turn of the 20th Century, two surgeons named Emerich Ullman and Alexis Carrel placed the kidney of goat into a dog. To their delight, and no doubt surprise, the kidneys continued to produce urine. One hundred years later, human organ transplants are commonplace operations – almost 4,000 were conducted in the UK last year – and animals are once again at the forefront of pioneering research to bring about the next revolution in transplant medicine.

Around the turn of the 20th Century, two surgeons named Emerich Ullman and Alexis Carrel placed the kidney of goat into a dog. To their delight, and no doubt surprise, the kidneys continued to produce urine. One hundred years later, human organ transplants are commonplace operations – almost 4,000 were conducted in the UK last year – and animals are once again at the forefront of pioneering research to bring about the next revolution in transplant medicine.

More than 10,000 people are currently in need of a new organ in the UK. Some lucky individuals get one within a few weeks, while others can spend years on the waiting list. Many tragically die before a match is found. And even when a suitable donor comes up, the transplanted organ will never work as well as it should; kidneys last between 10 to 15 years on average when transplanted, in addition to any complications caused by immune rejection.

Doctors and scientists hope that an emerging field known as regenerative medicine could change all this. By growing fully functional organs from a patient’s own cells, surgeons could have an unlimited supply of organs, free of any danger of immune rejection. The research is still in early stages but experiments using animals are showing great promise.

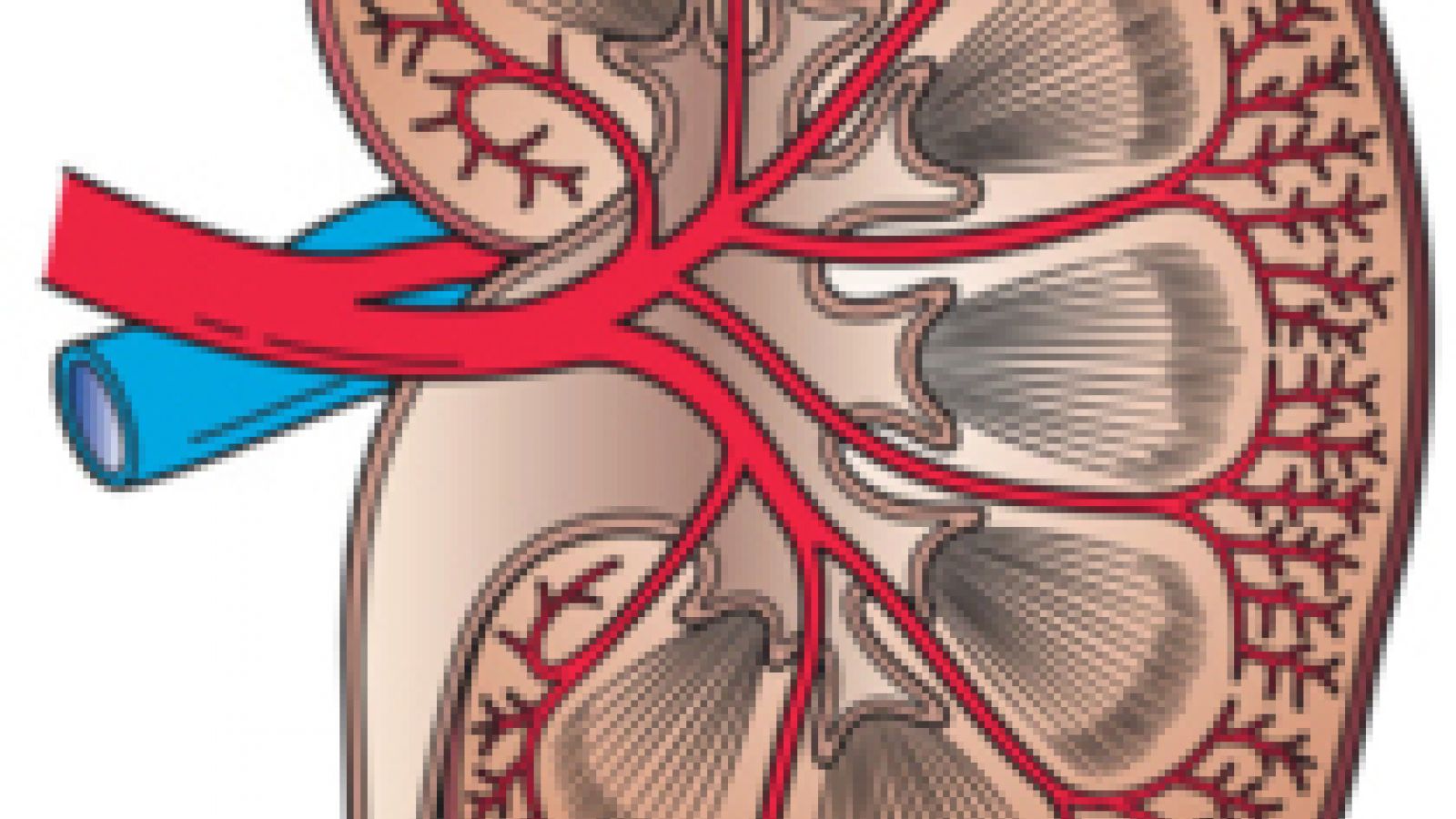

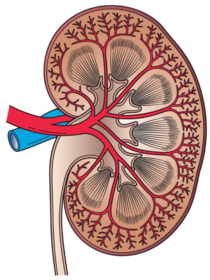

Last week scientists announced that they had successfully used rat cells to grow a functional kidney. The team responsible used an experimental technique that has previously been used to create working hearts and lungs. Rather than starting from scratch to build an organ, stem cells are added to a scaffold made from an organ stripped of functional cells using detergent.

In the latest work, kidney and blood vessel cells from newborn rats were added to the scaffold and cultured for 12 days as the cells multiplied to cover the scaffold, forming a functional organ. The kidney was then transplanted into a rat. With blood vessels and urethra reconnected, the kidney produced urine by filtering the rat’s blood, just like a normal kidney. The team have used the same technique with pig and human hearts showing it can be scaled up to larger organs, but they have not tested these in a living animal yet.

These results build on earlier bioengineering experiments aiming to make artificial kidneys. Previously, scientists have reported that cells taken from kidneys and cultured on blood-filtering artificial membranes replaced kidney function in dogs. And rudimentary kidneys grown without a scaffold from embryonic kidney cells showed limited success in rats, prolonging life compared to animals that did not receive a transplant.

Last year, regenerative medicine was announced as one of eight key technological areas in which the government wants the UK to become a world-leader. Like with Ullman and Carrel’s work a century earlier, animal research is essential to achieving this grand aim that could make organ waiting lists a thing of the past.

Last edited: 29 July 2022 14:01